Stroke Treatments

Current therapies, emerging trends

Stroke survivor Steve Kingsbury no longer plays golf, but he keeps his clubs around for occasional in-house putting.

Photographs by Lane Johnson

Imagine an earthquake in your brain. The shaking starts small and slowly becomes stronger, rattling your whole world. That’s what a stroke is like.

In Santa Clara County, 4,500 people each year are hospitalized due to a stroke. At age 47, Steve Kingsbury was one of those people. After playing a round of golf with friends, Kingsbury went to bed and woke up the next morning unable to move. A massive stroke took away his ability to walk and talk.

When a stroke—a blood clot in the brain—occurs, the blood supply is cut off and brain tissue begins to die. To stop the die-off, a fast response is critical. The stroke sufferer must get to the hospital immediately for emergency treatment or neuro-intervention in order to restore blood supply.

When Kingsbury awoke and realized he was having a stroke, he found that the entire right side of his body was numb, which prevented him from walking. His cell phone, which he normally put near his bed before going to sleep, had been left in the kitchen the night before.

“For just one minute I said, ‘This is scary,’ but that same minute I said, ‘You know what, I’ve got to find my cell.’ ”

Stroke sufferers who arrive at the hospital within three hours of when their symptoms first appeared may receive tPA, or tissue plasminogen activator. The only FDA-approved drug used to treat stroke, tPA is injected either into the vein or into the artery to break up the blood clot.

Not everybody is eligible for tPA, however, and Kingsbury was not. Because he had suffered a stroke while sleeping, there was no way to guess if the stroke had happened recently enough.

Ursula Kelly-Tolle, a registered nurse and Director of Neurovascular Services for Minimally Invasive Surgical Solutions in San Jose, says, “If you wake up with the symptoms, you don’t know if [the stroke] happened at 5 o’clock in the morning or if it happened at 10 o’clock at night.”

Since Kingsbury was not a candidate for tPA, the doctors’ next step was to begin neuro-intervention through one of several possible invasive procedures designed to break up the clot.

“With all of [these procedures], you’re working to try and remove the clot and restore blood flow to the blood vessels,” Kelly-Tolley says. A commonly used practice utilizes the Merci Retriever, a device designed by Concentric Medical in Mountain View. This corkscrew-like tool is inserted into the clotted vein, then pushed up into and past the clot. When the device is retrieved, it pulls the clot with it. “It’s very intricate work,” she says. “Highly skilled doctors have specialized in doing this type of work.”

Rebuilding Life After a Stroke

Many stroke victims suffer from long-term impairment, whether it is cognitive or physical. For Kingsbury, after his initial moments of clarity upon waking up, it took him four months of recovery to finally understand what was going on. “I couldn’t talk, but I had enough awareness. I thought, ‘Why am I not going to my place, where’s my car, where’s my life?’ ” he says.

“The brain has its own recovery time period,” says Dr. Allen Kaisler-Meza, Medical Director for the Inpatient Rehabilitation Program at the Mission Oaks Campus of Good Samaritan Hospital. “What we do is enhance that recovery.”

The Good Samaritan inpatient rehabilitation program provides three types of therapy: physical, occupational, and speech. Three-hour daily treatments are tailored to stroke patients’ individual needs.

“Some people who have had strokes don’t know they had a stroke. They don’t know why they are where they are. It’s that bad,” Kaisler-Meza says.

For patients like Kingsbury, speech therapy focuses on cognition, memory, language, and insight. In contrast, physical therapy for stroke survivors focuses on balance, standing, and walking. “Some people who have had strokes can move their arms and legs, but their balance is off. A physical therapist would work on their balance,” Kaisler-Meza says.

Often a stroke impairs a person’s ability to complete tasks associated with daily living. Occupational therapy helps survivors to relearn these basic tasks. “[Some patients] can walk, but they can’t use a bathroom,” says Kaisler-Meza. “The occupational therapist teaches them activities like combing their hair, brushing their teeth, taking a shower, going to the bathroom, dressing themselves, and eating.”

At Mission Oaks, the inpatient facility features a simulated apartment that helps survivors practice daily living tasks. “We feel very fortunate to have this apartment because patients can come to get the feel of home,” says Sondra Washam, a registered nurse and Community Education Coordinator for Rehabilitation Services at Good Samaritan. “It’s easier to do it when they get home if they practice it here.”

Seven years later and after a lot of therapy, Kingsbury has regained his ability to walk and talk, defying the predictions of some doctors who said he would never do either. He says his stroke granted him a unique perspective on life.

“I think if you live your whole life looking back, or if you’re looking in the future, you lose the minute—how beautiful it is,” he says. “I can just stop and say, ‘Wow, life is a mystery. It is a little bit scary sometimes, but I’m going to keep going because it really is special, and there is only one.’ ”

The Future of Stroke Therapies: Acupuncture and Stem Cells

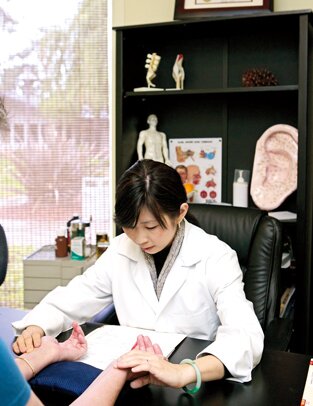

Currently in China, when a person suffers a stroke, he or she will receive emergency care similar to that in the United States, and then soon thereafter undergo a series of acupuncture treatments. Dr. Ching Ching Chi, PhD, L.Ac., an acupuncturist in Sunnyvale, says, “At this time not many people know that acupuncture can treat stroke or help alleviate a lot of symptoms that a stroke patient has.”

Chi cites one of her stroke patients who, after two treatments of acupuncture, was able to open her hand. After four treatments, another stroke patient was able to walk without her cane.

For stroke patients, Chi typically inserts needles in the head and on the extremities such as the hands and feet. “Acupuncture can help dilate the blood vessels and that will help to improve the circulation in the brain,” she says. “With head acupuncture, you can see immediate results.”

Ongoing studies on stem cell therapy also offer the possibility of advancements in stroke therapy. A study being done by SanBio, Inc. in Palo Alto involves injecting a cell therapy product called SB623, which is derived from mesenchymal stem cells, into the damaged area of stroke survivors’ brain tissue.

“Once [stem cells] are implanted, they promote the healing and regeneration of function in the tissue that has been damaged but not killed outright by the stroke,” says Dr. Casey Case, Vice President of Research at SanBio.

Mesenchymal stem cells are acquired from normal, healthy bone marrow donors, which make them ethical and easy to obtain. They also have a proven track record because they are used in bone marrow transplants. One bone marrow donor translates into thousands of doses of SB623.

“These cells are supportive in their regenerative properties,” Case says. “They don’t replace any of the tissue that’s been lost because of the stroke, but they encourage the healing and restoration of the part of the brain that’s been injured but not killed outright.”

Stem-cell therapy differs from tPA and neuro-intervention treatments because it attempts to promote the brain’s healing after it has stabilized following a stroke.

“This is important because many patients who have a stroke don’t get to the hospital within the few hours available,” Case says.

This first stage of the study will test the safety of the product, which is being evaluated at Stanford University in Palo Alto and the University of Pittsburg in Pennsylvania.